WHY NEW ITALIAN CINEMA IS HEADING TO A BRIGHT FUTURE.

Contemporary Italian cinema is invariably scarred by a self-inflicted inferiority complex. Melancholically lingering in the shadows of past cinematic glories, current film production does not always meet comparable quality standards and often fails to receive international recognition. A number of factors have contributed to shape a condition that, in the past few decades, has been variously described in terms of crisis: the lack of convincing screenplays, the pressures of the market, political and economic impediments, and – last but not least – the inadequate film literacy of the Italian audience, largely unwilling to engage non-mainstream products. However, by giving up preconceived pessimism, we realise that the situation is not unrecoverable and that the margins for hope are broad enough to envision a brighter future.

One recurrent feature in their works is a specific focus on regional contexts and local issues. In the most significant cases, this is rarely reduced to folkloristic purposes, but rather turns regional settings, countryside villages, and urban enclaves into privileged outposts for a close study of the Italian society in transformation.

Set in the rundown Southern city of Reggio Calabria, Alice Rohrwacher’s 2011 debut feature Corpo Celeste (realised by Italian London-based producer Carlo Cresto-Dina) is an affecting coming-of-age story, which cleverly investigates issues of teenage uneasiness, mass culture, and spiritual alienation. The film’s widespread critical acclaim has possibly paved the way for Rohrwacher’s second feature, The Wonders, to enter Cannes main competition this year, where it grabbed the Grand Jury Prize. Focusing instead on specific Sicilian features, renowned theatre director Emma Dante made her silver-screen debut in 2013 with a Street in Palermo. The film stages a gendered fight of wider human relevance: what at first appears as an instinct-led collision between two stubborn women subtly develops into an act of female resistance against a world dominated by male control. Sicily is also the distinctive set of Fabio Grassadonia’s and Antonio Piazza’s 2013 debut feature Salvo. The film powerfully rethinks the ‘mafia movie’ genre through the story a cold-blooded killer and his potential victim, a blind girl who miraculously regains sight. Art-house cinema in its purest form, Salvo delivers a rich sensorial experience with its combination of haunting long takes and evocative cinematography.

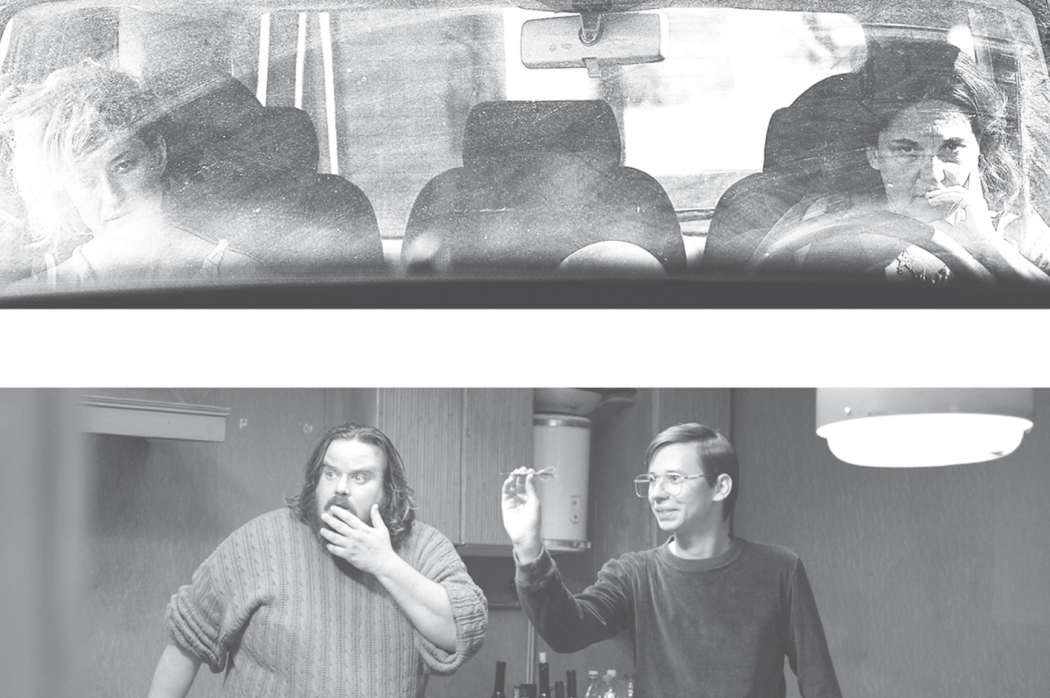

This latest wave of Italian cinema is not limited solely to the dramatic: comedies keep on playing an important role. Matteo Oleotto’s 2013 Zoran, My Nephew the Idiot, for instance, amusingly narrates the awkward relationship between a drunken uncle and his seemingly idiotic nephew, who eventually proves a phenomenal master of darts.

Making the most of their background in documentary and video art, the filmmakers combine an insightful exploration of social reality with a stunning display of aesthetic self-confidence. Concerned with questions of cultural integration, Andrea Segre’s films are another case in point. Set within milieus of particular local relevance, his works blend realist truthfulness and poetic hints: Shun Li and Poet (2011) tells of the tender friendship between a Chinese bartender and an old fisherman in the Venetian lagoon; First Snowfall (2013) investigates the delicate connection between a Togolese refugee and orphan boy in a village in the Alps.The film is the ravishing example of a comedy that, while remaining viewer-friendly, does not give up narrative subtlety and visual refinement. This last example can be more generally seen as representative of the variety of this young Italian cinema and further testifies to the inherent complexity of these works. Although low-quality mainstream works still dominate the national box office, these filmmakers are sending out strong signals against artistic standardisation and cultural bulldozing. And the future of Italian cinema now looks a little brighter.